Disaster Accountability in Nepal

Written by: Data Shift

On 25 April 2015, an earthquake measuring 7.8 on the magnitude scale struck Nepal, a major aftershock occurring on 12 May. These massive quakes killed more than 8800 people, injured over 21,000, damaged nine million homes and pushed 2.5% – 3.5% of the population back into poverty.

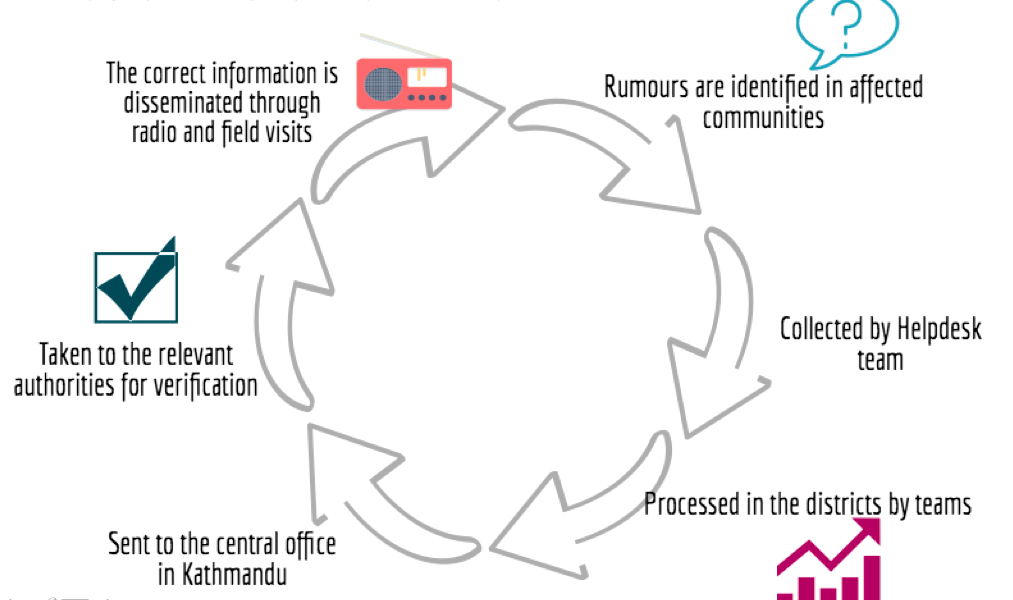

In the wake of these devastating earthquakes in Nepal, the Nepalese government and other actors turned its attention to humanitarian assistance. Aiming at monitoring and improving earthquake response, Local Interventions Group (LIG) together with Accountability Lab (AL) started the Mobile Help Desk, an initiative that would close the information loop that exists between the public and the government while simultaneously, plugging these gaps by directly providing essential information to earthquake victims.

On 10 August, DataShift hosted a Community Call, inviting Quincy Wiele from Local Interventions Group (LIG) and Sara Rodriguez Accountability Lab (AL) to share their experiences in providing opportunities for Nepalese to be more involved in the disaster recovery process and holding their government accountable.

Local Interventions Group uses data to promote better governance and have previously used data for security mapping with the police and tracking district official absenteeism. The Accountability Lab works to promote accountability and transparency to reduce corruption building a new generation of active citizens and responsible citizens around the world. Together they started the Quake Help Desk.

After a natural disaster, the international community and citizens are often generous with financial support for survivors. That money however, is entrusted to the government; often with no strings attached. When governments are given a blank check for disaster relief and recovery, how can citizens hold them accountable for how that money is spent? In response to this, the Quake Help Desk conducted earthquake-related activities such as;

- providing advocacy related information to citizens rights regarding earthquake relief,

- conducting community perception surveys,

- connecting citizens with different organisations,

- tracking rumours,

- providing earthquake-related information,

- monitoring the finance flows,

- encouraging communities to discuss on the state of post-earthquake responses, and

- making sure that people in localities are receiving the support they have been promised.

Through these range of activities, LIG and AL were able to close the loop on the earthquake response in Nepal. Their disaster accountability work called “Follow the Money”, allowed them to track relief disbursement into 14 affected districts, down to the village level. The collected data was analysed, cleaned and visualised on an online platform, with the objectives of:

- reducing corruption, through providing empirical evidence to the government of funding irregularities,

- strengthening public capacity, and

- raising awareness by reminding citizens of their entitlements.

One way of tracking, involved conducting community perception surveys. Through these surveys they found that by listening to people’s needs and comparing the discrepancies between districts, the humanitarian community was able to adapt its response to specific circumstances – improving the overall earthquake response.

In order to close the feedback loop, their “Open Mic Project” ensured that people had access to correct earthquake related information, thus reducing the potentially harmful/inflammatory impacts of incorrect information.

Through these activities, LIG and AL were also able to have an impact beyond their initial objectives. They mobilised over 100 volunteers, hired more than 100 community frontline associates, exposed more than 80,000 people and monitored more than 1,000 villages; identifying over 20 different issues. Over 25 humanitarian organisations and government agencies are using the data.

Quincy and Sara also shared their findings with us during the call. It was clear that transparency and accountability lacked at every level. Their work also showed that during the first eight months after the earthquake, negative perceptions about relief and the reconstruction process remained consistent, with slight improvements noticed after this period. In July 2016, 79% of people felt their reconstruction issues were not being addressed, showing that the reconstruction process is still viewed unfavourably. Initial data from “Follow the Money” showed that significant funding discrepancies existed and that significant levels of corruption existed in the relief process.

The team was also confronted with challenges, such as; managing high expectations as it was sometimes difficult to ask for data without providing tangible assistance to victims. Communication was key for overcoming this, as the team worked hard to build trust within the communities. Accessing remote communities also posed as a challenge, however, by hiring locals or being close to survey areas to minimise journey time – they found a way around it. Another challenge they encountered was survey fatigue, with more than 12 organisations doing similar work. It was thus difficult to convince the community that they would benefit from continuously sharing their experience.

Quincy and Sara have learnt that in these situations, you have to strike while the iron is hot, as it is difficult to continue mobilising for earthquake response, when it is already considered “old news”. They also learned the importance of building good relationships with the government, which ultimately gave them more leverage. By avoiding pointing fingers at government and humanitarian agencies, they have managed to maintain a positive approach to their work. Going forward, LIG and AL are developing a toolkit with lessons learned to be shared with other countries facing similar situations and hope that this model can be replicated for other disaster accountability.

This article was originally published by Civicus