Foreign Direct Investments in Nepal

Written by: Samata Shrestha

Samata was a participant in the Blog-Writing Competition on Democracy, Geopolitics, and Foreign Affairs organized by Accountability Lab Nepal, and she was selected as one of the winners from over 50 submissions.

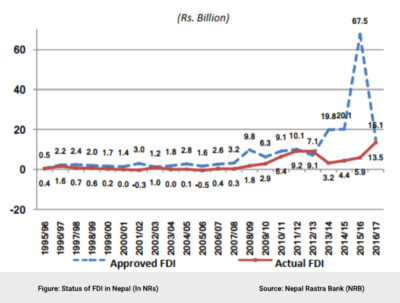

Nepal’s low absorptive capacity for foreign aid, as well as foreign investments, has been evident when compared with other similarly situated countries in South Asia (Lohani, 2016). After April 2015 Nepal Earthquake, a great number of foreign investment commitments was made. Such pledges were not translated into real monetary investments. Nepal has received billions of rupees worth of commitments and pledges from foreign investors but the actual Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has been significantly low. For the financial year 2015/16, there were FDI pledges of Nepalese Rupees (NPR) 15.13 billion (approx. $136 million) but the actually received amount was only NRP. 5.92 billion (approx. $53 million) (Nepal Rastra Bank, 2018). It is not a one-time event that such a mismatch in pledges and actual investments has occurred. Instead, it shows a continuous pattern of the gap between the two. The objective of this writing is to investigate why such a situation persists by analyzing the reasons behind the lag between FDI commitments and actual investments in Nepal.

Nepal shared only 0.01% of total FDI in the world in 2016. The total percentage of net inflow of actual FDI was 0.48%, 0.38%, 0.15%, and 0.24% of GDP in 2012, 2013, 2014, and 2015 respectively (Nepal Rastra Bank, 2018). When we observe the FDI flows in Nepal, it only received around 1 million dollars as FDI flows in the pre-crisis years i.e. between 2005- 2007 (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2018). However, there has been a general increasing trend of FDI flows in Nepal and South Asian region in general.

The hierarchical nature of the system has established a requirement for a multitude of clearances and approvals where the power is concentrated in the central government. Under Foreign Investment and Technology Transfer Act (FITTA), the procedure to obtain approvals has been even more complex and cumbersome with the formation of three hierarchical institutions of Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), Investment Board Nepal (IBN), and the Department of Industry (DoI) to clear approvals based on the amount of investment. For more decentralization of power, greater freedom to provinces without limiting the power to the central government is required which would allow healthy competition among themselves (Bajpai & Sachs, 2000). China can be exemplary where regional governments have a leading role in promoting reforms and actions by the central government. The coastal provinces in China and the provinces farthest from Beijing have been a major stimulus to reforms in the central government.

Delays in approvals and squandering time from one government office to the other make Nepal a less viable option as the investors have options to invest in other numerous emerging markets in South Asia. Removal of competitive disadvantage i.e., the multilayer of FDI approval system would be a progressive step to convert large sums of FDI commitments into actual monetary funds. For Nepal to be investor-friendly, the lengthy paperwork needs to be reduced along with delayed approvals in bringing FDI. The prolonged implementation time of the projects has had a negative impression on foreign investors. Since Nepal lacks an effective one-stop agency, the investors are compelled to deal with various line ministries and their departments for getting paperwork done. It is a time-consuming process with inadequate coordination between them for project approval. Nepal needs to ensure that agreements, policies, and documents that are implemented are simple to navigate and easy to follow (Chalise et al., 2014).

Almost all countries in South Asia have a one-stop approval or an automatic route for FDI approval in priority sectors except Nepal which has a bureaucratic two-layer approval system for FDI. In an automatic route system, there is no requirement for approvals from the government to bring FDI into the approved sector which enables a faster and more efficient flow of foreign investment. Instead, investors need to submit a hefty list of documents first to DoI for approval, then another long list of documents to NRB for approval, and only then investors can transfer investment amounts to Nepal. Furthermore, the approval process is extended depending on the investment amount where IBN must approve a project before DoI can issue a letter to NRB for approval (Satyal, 2017).

New policies introduced by government agencies under FITTA (Foreign Investment and Technology Transfer Act) have been progressive, but it is not enough. It is because the main problem lies in the implementation side of such regulations. Although FDI rules are constantly updated, they would have little meaning if they cannot be implemented in an organized manner. The government agencies have their own interpretation of the regulations and as a result, such policies do not translate well. Lack of coordination between different government agencies and their interpretation of their own versions of the policies (such as getting approvals) has caused delays and withdrawals in national as well as international projects. The hierarchy has resulted in a concentration on regulation and control rather than creating a facilitating environment for investors. This creates layers of rules and regulations instead of achieving harmony between these laws. It is important to acknowledge that regulation is not only for controlling and administering but also for facilitating the investors.

Despite new laws and regulations, Nepal has not been able to convert huge financial commitments of FDI into real monetary investments. Even though Nepal has been receiving an increasing amount of FDI after 2007, the amount remains very low compared to other South Asian countries. The major issue is that there remains a huge difference between approved FDI and the actual FDI that Nepal receives. The foreign-invested projects tend to invest in large-scaled and long-time lead projects which are capital and infrastructure intensive. It could ultimately lead to the withdrawal of the project or the project being incomplete and delayed. Such factors lead to a negative impression on the foreign investors which has led Nepal into a no-option trap of expensive projects and hence creates low absorptive capacity for foreign aid, as well as foreign investments. Efforts in building a favorable investment climate that encourages national as well as foreign investors need to be consistent to attract and sustain FDI in Nepal.

References

- Bajpai, N., & Sachs, J. D. (2000). Foreign Direct Investment in India: Issues and Problems. Retrieved from https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8CV4QMB/download.

- Chalise, B., Nepal A., Pant A. (2014). Nepal’s Foreign Investment Policy and its Implication to Investors. Kathmandu: Samriddhi Foundation.

- Koirala, J. (2018, April 3). SAFTA and Nepal: Time for paradigm shift. The Himalayan Times. Retrieved from https://thehimalayantimes.com/opinion/safta-and-nepal-time-for-paradigm-shift/.

- Lohani, P. C. (2016). Nepal’s experience of foreign aid, and how it can kick the habit. In D. Gyawali, M. Thompson, & M. Verweij. Aid, Technology and Development: The lessons from Nepal (pp. 203-217). London: Routledge.

- Nepal Rastra Bank (2018). A Survey Report on Foreign Direct Investment in Nepal. Retrieved from: https://www.nrb.org.np/red/publications/study_reports/Study_Reports– A_Survey_Report_on_Foreign_Direct_Investment_in_Nepal).pdf.

- Satyal, S. (2017, March 15). Transforming FDI: Automatic route. The Himalayan Times. Retrieved from https://thehimalayantimes.com/opinion/transforming-foreign-direct-investments-automaticroute/.

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2018). World Investment Report. New York, Geneva: United Nations.