Five Things We’re Doing To Fight Back Against Closing Civic Space In West Africa

By Kibo Ngowi

West Africa is a rich and diverse part of the world-spanning 16 countries and boasting an estimated population of close to 400 million people. Accountability Lab has deep roots in the region, having established our second network Lab in Liberia back in 2013, only a year after the organization’s birth in Nepal.

We’ve since opened more Labs in Niger, Nigeria and Mali and with the support of Observatório da Democracia e Governança we’ve rolled out our Virtual Incubator program in Guinea-Bissau as well. These efforts are a response to the governance and stability challenges in the region as demonstrated by the recent instances of domestic terrorism in Nigeria and the ongoing military rule in Mali.

Civic space has been under increasing pressure in all the West African countries in which we operate but our resilient team members and the passionate young civil society leaders in our network have found innovative ways to hold those in power accountable and inspire citizen engagement throughout. These are just some examples of the work we’re doing to fight back against the closing democratic and civic space in West Africa.

Young people between the ages of 18 and 35 account for a large percentage of Liberia’s population but are largely excluded from local development and peace building processes, which means their voices are not heard in these activities at the local and national levels.

“Even where young people are involved in the informal process through civil society, they lack the right skills or the networks and platforms through which to engage with other stakeholders – such as the policy experts or lawmakers – to influence policy making,” says Nyema J. Richards, AL Liberia’s Director of Programs and Learning.

“Incorporating youth voices in peace and security will require concerted efforts to provide them the right spaces, tools and skills for them to actively engage in development and peace building processes.”

In an effort to address this situation, the AL Liberia team supported 10 local youth-led organizations from five strategic counties: Montserrado from central Liberia, where about a fourth of all Liberian residents reside; Grand Gedeh County, a hub of the south-eastern counties; Nimba County, northern Liberia, a populous area with quickly growing commercial activities; Bomi County, a hub for the western counties; and Grand Bassa County, in southern Liberia.

“The most significant outcome of the project was that, as a result of our seed funding, 10 peace-related campaigns, two in each of the five counties were either launched or existing campaigns strengthened,” says Richards.

“Furthermore, all 20 participants in the capacity building bootcamp reported increased skills and knowledge related to peace-building and other contextual content covered during training. A peace alliance network was formed with 20 members from the five counties, and 80% of the members reported substantive plans to collaborate on peace-building initiatives.”

A training manual was also produced for use by youth organizations. The manual is designed to guide national youth organizations in engaging national and local governments, and to support civil society and other relevant stakeholders to engage around critical issues of inclusive, peaceful governance.

Finally, a national stakeholders forum was held through which recommendations were provided to local and national leaders. The forum included representation from the national legislature, tribal authorities, the United Nations Development Program, the Federation of Liberian Youth, the national media and other civil society organizations. All of this work builds upon our efforts ahead of the Liberian elections in 2017 to engage young people in peace-building.

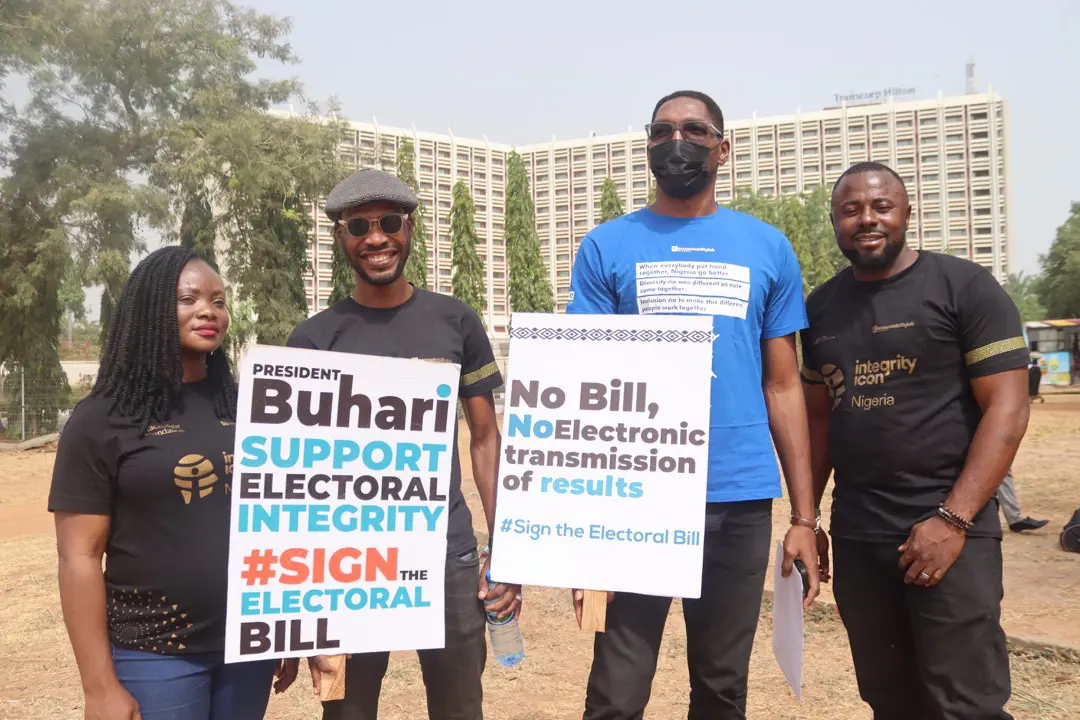

In January 2021, just 10.3% of ministerial positions were held by women in (three out of 29) and just 5.8% of parliamentary seats were held by women- thus ranking Nigeria 149th (out of 155 countries) on political empowerment in the 2021 World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report. A lack of equal representation in decision-making structures is a common problem throughout West Africa and the global south for various reasons, but AL Nigeria has identified one crucial reason this status quo remains entrenched in Africa’s most populous country.

The high cost of obtaining party nomination forms keeps underrepresented groups such as women, youth and people with disabilities from contesting elections. The AL Nigeria team’s Gov-Her-Nance program is aimed at promoting women’s civic participation and inclusive gender-sensitive policymaking at both local and national levels. As part of this program, the team hosted a series of radio programs where members of the public shared their perspectives on what can be done to achieve greater levels of inclusion.

One of the most interesting pieces of feedback from these engagements was the insight that many of the policies hindering the representation and participation of marginalized groups in Nigeria’s governance structures have been instituted by political parties. Recently, some political parties have set the price of their nomination forms for the upcoming 2023 elections at millions of naira, politically excluding thousands of Nigerian citizens.

In a similar vein, the Nigerian Senate approved an increase in election campaign spending across the board – up to 400% in some cases – allowing spending of up to 5 billion naira for presidential candidates and 1 billion naira for Governorship aspirants. This systemically casts women, youths and PWDs, who are already in a financially disadvantaged position, further from representation and participation in decision-making processes. One of the solutions suggested was the formation of political pressure groups by marginalized citizens to make their voices heard.

“From the communications end, we are developing content around the forthcoming elections for our social media platforms to inspire citizens to get their Permanent Voters Card, vote for a credible candidate, “vote not fight” and “don’t sell your vote” among other election themes,” says Prince Chiramoke, AL Nigeria Communications Officer.

“Beyond this, we are working with Well-Versed to begin a monthly music challenge to get young music artists to develop music around election themes and support the winners to come into the studio to produce the selected song for the month. The produced songs will be shared online on music streaming platforms and with some of our radio partners.”

Shiiwua Mnenga, AL Nigeria Project Officer, adds: “We are currently running a project which focuses on inclusion and gender and we have been having sessions on access to public buildings by PWDs in line with the provisions of the Prohibition Against Persons with Disabilities Act in Nigeria. We have also been supporting the passage of the Gender and Equal Opportunities Bill before the National Assembly.”

Last month, Guinea-Bissau’s President Umaro Sissoco Embalo dissolved the country’s parliament and said early parliamentary elections would be held by the end of 2022 to resolve a long-running political crisis. Tension between parliament and the presidency has been a source of problems in the West African state for months. Eleven people died in February in violence that was described as an attempted coup.

“In Guinea Bissau, I believe there is no space for the common citizen,” says Artemiza Bucansil Cabral. “The only voices given space are those of the politicians in power and their supporters, in ways that this practice has become a vicious cycle. To ban this practice, it is necessary to change behavior, starting with the common citizen.”

Cabral is an accountapreneur of our first Accountability Incubator cohort in Guinea-Bissau and a journalist reporting on National Television in Guinea-Bissau. She holds the position of Director of Communications and External Communications at the Guinea-Bissau Court of Accounts and has collaborated with different civil society organizations on issues related to women’s empowerment.

“It takes an ongoing struggle and global awareness of gender because what a man does, a woman can also.” she says. “Even so, in a sexist society where women continue to be marginalized, the thing that must be lived is continuing the struggle so that all women can live freely and equally with men.”

Cabral is passionate about women’s rights and she has participated in training courses in the field of women’s empowerment and participation in decision-making. Through her incubator project, Emancipação das Mulheres (Emancipation of Women), she wants to address the disparity of opportunities between genders and contribute to a more equal society.

She created a television program called “Mulher em Foco” (Women in Focus) where she explored gender issues in Guinea-Bissau through conversations with women from different walks of life. It aired for one season and received positive reviews so she plans to continue it in future. She also collaborates on various initiatives with the main women’s organizations in the country, including UN Women.

“With the dissolution of parliament, the participation of women and other vulnerable groups was postponed once again,” she explains. “If before they had no participation, now it has become even worse. Women are always relegated to the background in decision-making. Even when the parliament was dissolved, the political parties were convened for consultation, but no women-focused civil society organization was invited. Serious dialogue is needed in this regard.”

“Two of the root causes of the Malian crisis identified by citizens as an obstacle to peace are poor governance and the poor distribution of justice, sometimes in areas particularly exposed to crises where competition for resources is poorly regulated and can be a catalyst for conflict rather than for security and social cohesion,” explains Dramane Fofana, AL Mali’s Civic Action Teams (CivActs) Program Officer.

“This disconnection between the government and the governed partly explains the rise of centrifugal forces – including Islamists and bandit groups – which use this argument to establish their hold on populations that are sometimes distraught and thirsty for social justice, which they believe only these groups dissident from the state are able to provide.”

“All these factors are known, as is the lack of trust they generate in the relationship between the government and the governed. The question is how to reduce them and improve mutual trust between the actors mentioned.”

AL Mali is currently using our pioneering citizen feedback CivActs model to implement the project “Strengthening Trust, Social Cohesion and Resilience between Citizens and Power Holders in the Central and Northern Regions of Mali.” The team recently conducted a mission to the localities of Gao, Ansongo and Ménaka, Timbuktu, Mopti-Sevaré and Toya in the rural commune of Alafia with the objective of meeting with key stakeholders for the establishment, identification and training of Community Frontline Associates (CFAs) for the implementation of the project.

“These are the regions of the country where the legitimacy of the state is weak, and where the power of the government is limited and contested by armed groups,” explains Fofona. “Through this project, we will focus on identifying the root causes of the trust deficit between citizens and those in power in these regions.”

The team met with local authorities including village chiefs, imams, communal authorities, mayors, governors, directors of departments and community radio hosts to present the project’s objectives.

Some of these objectives are to address grievances arising from the conflict and support cohesion and trust-building within and between communities and governors; strengthen trust between authorities and citizens through participatory structural dialogue to diagnose the root causes of the trust deficit and explore possible solutions, and establish a system for capitalizing on lessons learned and good practices with a view to extending the initiative to other localities in the country.

“After the presentations, the authorities expressed their support and pledged to participate as the project is in line with the problems experienced by the populations, and made recommendations and pointed out certain problems,” says Fofona. “In return, they said they were pleased with the arrival of such a project in the current context of their locality and of Mali in general.”

“The local authorities told us that any project that aims to strengthen cohesion within their community is welcome and that their support and advice will not be lacking. Whenever the need arises, they will be at our disposal for the development of their community.”

During the mission, the team also trained 30 young CFAs, comprising 12 women and 18 men, on accountability, governance and leadership; the use of KoboToolbox, an app for data collection; how to talk about the work of AL Mali; discussing the CivActs program; and discussing the project itself. After this training, each of the CFAs received a device that will be used to carry out data collection throughout the project.

“Niger’s civic space has been classified as “obstructed” since 2018 due to immediate and urgent threats to the country’s civic space,” says AL Niger Country Director Oumarou Adamou.

“We have noted several key violations of civic space over the last few years including the passage of repressive laws, including the 2020 Law on Interception of Electronic Messages (2020); Misuse of the Anti-Cybercrime Act of 2019 for judicial harassment and prosecution of human rights defenders, especially journalists; and a systematic ban on civil society demonstrations, as well as excessive use of force and arrest of peaceful protesters.”

Adamou led the Nigerian Anti-Corruption Network along with other Nigerian CSOs in filing a denunciation complaint following the Court of Auditors report in May at the Niamey High Court. This denunciation complaint is part of a sustained effort by Nigerien civil society to force President Mohamed Bazoum to honor his commitments to the Nigerien people.

“It is a question of challenging the president of the republic to make good on the promises he made to the people of Niger during his investiture to the supreme magistracy of the country and the promises he made to civil society during the two meetings at the Presidency of the Republic,” explains Adamou.

“The President publicly insisted that anyone who has a responsibility in public administration would henceforth be solely and entirely responsible for their actions and that corrupt behavior would be swiftly punished without fear or favor. Furthermore, he demanded that all officials at the different levels of the administration be promoted solely on the basis of their technical competence and their morality.”

Adamou believes the courts are a good tool for holding power holders to account if they properly exercise their duties and follow the constitution which stipulates that “justice is rendered on the national territory in the name of the people and in strict compliance with the rule of law” and that any act of sabotage, vandalism, corruption, embezzlement, dilapidation, money laundering or illicit enrichment will be punished by law.

“We believe that the courts are obliged, in the name of the separation of powers, to hold those in power accountable for their commitments, because the only bulwark between the governors and the governed is justice,” he says. “This justice must be free and independent in its decisions and any act or decision must be taken in the name of the people, for the sole interest of the latter and not in the name of any person or third party.”

“The recent corruption case involving the former Minister of Communication is part of a batch of embezzlement and economic delinquency instances that we have taken to the courts to pressure those in power. To that we can add the case of the Ministry of National Defense known as MDNGate in which even the main actors have not been condemned; some have been questioned and reimbursed the overcharged funds and undelivered materials (according to the prosecutor).”

“But at this level, much remains to be done because the administrators who were accomplices and co-authors have not been questioned, even though there can be no corruptor without a corrupted person and no entrepreneur or trader without the complicity of the administrators, i.e., those in charge of awarding contracts, controllers, and those responsible for authorizing expenditures.”

Much remains to be done at the level of protecting civic space in Liberia, Nigeria, Guinea-Bissua, Mali and Niger and West Africa as a whole but the kinds of efforts outlined above can begin to move the needle forward.

As the last pan-African revolutionary and statesman Kwame Nkrumah once remarked: “Countrymen, the task ahead is great indeed, and heavy is the responsibility; and yet it is a noble and glorious challenge – a challenge which calls for the courage to dream, the courage to believe, the courage to dare, the courage to do, the courage to envision, the courage to fight, the courage to work, the courage to achieve – to achieve the highest excellencies and the fullest greatness of mankind.”

Kibo Ngowi is the global Marketing & Communications Officer for Accountability Lab, a global translocal network that makes governance work for people by supporting active citizens, responsible leaders and accountable institutions. Read the original article in Sahara Reporters.